Environment

Deep-rooted and completely erroneous preconceptions of our planet’s arid lands

as sterile bit-players in the great game of the earth’s dynamic systems have

long inhibited our scientific enthusiasm for, and understanding of, the

desert. We are now beginning to catch up – take, for example, this recent

headline from the American Geophysical Union:

The world’s deserts may be storing some of the climate-changing carbon

dioxide emitted by human activities, a new study suggests. Massive aquifers

underneath deserts could hold more carbon than all the plants on land,

according to the new research.

As described in a summary of this research

on Science Daily :

Humans add carbon dioxide to the atmosphere through fossil fuel combustion

and deforestation. About 40 percent of this carbon stays in the atmosphere

and roughly 30 percent enters the ocean, according to the University

Corporation for Atmospheric Research. Scientists thought the remaining

carbon was taken up by plants on land, but measurements show plants don’t

absorb all of the leftover carbon. Scientists have been searching for a

place on land where the additional carbon is being stored–the so-called

“missing carbon sink.”

The lead author of the report in the AGU publication,

Geophysical Research Letters, is Yan Li, a desert biogeochemist with the

Chinese Academy of Sciences in Urumqi, Xinjiang; he and his team examined the

character of groundwaters in the gigantic closed system of the arid Tarim

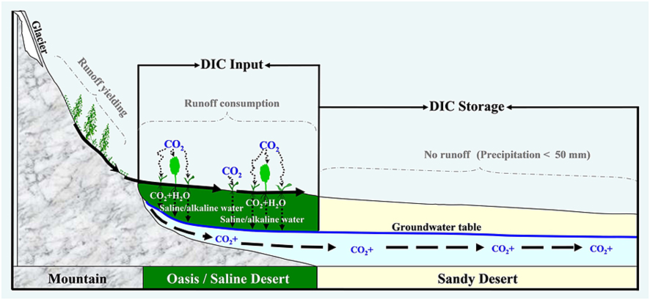

Basin, and came up with some fascinating – and provocative – results. Runoff

waters from the surrounding mountains pick up, as a normal part of the carbon

cycle, some CO2 dissolved from the rocks and soils through which the rivers

flow. However, by the time that water ends up in aquifers, the underground

reservoirs beneath the desert, it contains substantial amounts of DIC,

dissolved inorganic carbon.

Being able to date the carbon, Li and his colleagues could distinguish between

old carbon originating from the rivers and very young carbon added to the

water as it seeped through the soils of the irrigated oases along the desert

margins. These are poor soils, not in themselves sources of much CO2 - it

originates from the respiration of the roots of crops and microbes in the

soil. And because these crops are irrigated almost constantly, not only to

keep them growing but to wash out the salts that, as in all desert

agriculture, accumulate in the soil, most of the CO2 is transported downward

into the groundwater moving out below the desert to be trapped in the deep

aquifers. Importantly, because of the salts, these waters are saline and

alkaline and the solubility of CO2 in saline/alkaline water is much higher

than in pure or acidic water – the desert groundwater is a very significant

CO2 sink.

Because of their ability to date the carbon dissolved in the waters, the

researchers were able to establish that the levels jumped substantially in

historical times as the development of the Silk Road enabled the beginnings of

oasis agriculture. Man’s activities – irrigation and over-irrigation – have

augmented the efficiency of this carbon sink by, it is estimated, a factor of

twelve:

Based on the various rates that carbon entered the desert throughout

history, the study’s authors estimate 20 billion metric tons (22 billion

U.S. tons) of carbon is stored underneath the Tarim Basin desert, dissolved

in an aquifer that contains roughly 10 times the amount of water held in the

North American Great Lakes.The study’s authors approximate the world’s desert aquifers contain roughly

1 trillion metric tons (1 trillion U.S. tons) of carbon–about a quarter

more than the amount stored in living plants on land.

And because this is a saline and alkaline aquifer, the water is completely

unsuitable for agriculture – it will likely remain below the desert as

essentially permanent carbon storage - undoubtedly not the only missing sink,

but a hitherto unidentified one. As Li remarks: “The fact that such a huge

carbon pool and active sink has been unstudied for so long may simply be

because it is remote and hidden under deserts: out of sight, out of mind.”

[Image at the head of this post is of agriculture and dunes along the northern edge of the Tarim Basin, Google Earth; diagram of the process of carbon

storage from Yan Li, Yu-Gang Wang, R. A. Houghton, Li-Song Tang. Hidden

carbon sink beneath desert. Geophysical Research Letters , 2015;

DOI:10.1002/2015GL064222]

Originally published at: https://throughthesandglass.typepad.com/through_the_sandglass/environment/page/2/