Science

It’s this year’s Earth Science Week - see the American Geosciences Institute

and Geological Society of London

sites). I have periodically attempted to join the celebrations with posts on

the “[Nine big ideas](https://throughthesandglass.typepad.com/through_the_sandglass/2009/10/earth-

science-week—sand-and-the-nine-big-ideas.html)” and the [associated videos](https://throughthesandglass.typepad.com/through_the_sandglass/2012/10/earth-

science-week-the-big-ideas-videos.html), [Earth Science Literacy](https://throughthesandglass.typepad.com/through_the_sandglass/2010/10/earth-

science-week-and-earth-science-literacy.html), and the outstanding “[known unknowns](https://throughthesandglass.typepad.com/through_the_sandglass/2014/10/earth-

science-week-2014.html)” of earth science - please have a re-visit.

These were largely ruminations on what geology is about, the “philosophy” of

the science, and a little advocacy for greater awareness. The question of

why geology, what makes it fascinating, were subtexts, so my attention this

year has been caught by a piece from September 2015 by Julia Turner, editor in

chief of Slate. Titled “Your World, Rocked: A good introduction to geology

course is actually a course in time,” it is an eloquent (and personal)

testimony to the value (sometimes not so obvious) of even a modest exposure to

how our home planet works. It is, of course from the perspective of US

education, but that matters not at all - its message is universal. The “rocks

for jocks” amusement in the introduction is purely American - and so true. I

taught Geology 101, otherwise known as “rocks for jocks” for several years,

with many rewards and frustrations. Chief amongst the latter were the many

kids who told me how much they enjoyed it, having had no idea at all about

geology, and regretted that they were too far down their academic path (having

left the science requirement until last) to pursue it further. I doubt that

problem has gone away - to the loss of the science. There were many kids who

were a joy to teach and interact with (although here I do not include the

young woman who entered my office, closed the door, and declared that

“Professor Welland, I’d do anything for an A”). But I digress…

In celebration of Earth Science Week, and in the hope that it might persuade

just one young person to take a geology class, I am taking the liberty of

reproducing in its entirety Julia Turner’s piece from

Slate:

A good introduction to geology course is actually a course in time.

By Julia Turner

Let me start by defending geology’s honor. Is there any other discipline

that a rhyme so easily reduces to ridicule? Nearly every campus has some

version of “rocks for jocks,” the intro geology course touted as the easiest

way for granite-brained humanities majors to fulfill their science

requirements without significant intrusion on their time or erosion of their

GPAs.But you shouldn’t take geology because it’s easy. (It isn’t necessarily

easy—the geology class I took, from a bright-eyed elfin woman with the

pleasing, rocklike name of Jan Tullis, certainly wasn’t.) You should take

geology because it will fundamentally transform the way you see the world.I mean this literally. Understanding geology gives you a new way to

interpret the visual data of the planet. Sometimes this can feel like X-ray

vision or a sixth sense. The color of the soil can tell you what it’s made

of. The lightning bolts of white across that cliff the highway blasted

through? Quartz veins, a sign of metamorphic activity, way back, when

fissures opened up in bending, cracking stone, and mineral-laden water

coursed through. Looking out of a plane window at the contours of a mountain

range, you can tell from shape alone whether the peaks are old or new—or

rather, which are very very old and which are just old. (It’s the opposite

of human aging: cragginess is a sign of relative youth, and smoothness comes

only with time.) And the words! Schist. Nickeliferous. Gneiss. Each one with

its own dense poetry.Geology helps the land tell you stories. I remember flying once and noticing

funny little slab-like mountains, each one distinct from the next, lying in

parallel rows. Where once I would have seen only mystery, now I could

imagine how those mountains came to be—a sedimentary bed, layer upon flat

layer of different types of rock, broken and thrust upward by the movement

of the plates, revealing a cross section in which the softer rocks had

eventually eroded away, leaving only these orderly little slabs.Geology is a gorgeous way to contemplate the abyss.

But geology does more than give you something to think about when you

examine pebbles on a beach or go swimming in a quarry. You should also take

geology because there is no better way to gain perspective on the

fleetingness of life. Any good intro geology course is actually a course in

time. You’ve heard the statistic: If the whole planet has been around for a

single 24-hour day, the dinosaurs showed up at 10:56 p.m. and we just before

11:59. But imagine spending hours holding that thought in your mind,

learning what happened during all the time that preceded us. Understanding,

in a real way, how long the planet has been around; how slow, patient, and

indifferent the movement of the rocks beneath us has been; how insignificant

in the scheme of things our fervid civilizations and wars and inventions

really are—this is a head trip better than any you’ll experience during the

concert at Spring Fling…Taking geology actually had a funny side effect for me. I came into the

class an avid environmentalist. I was a child of the ’90s. I cared about

whales. I recycled. I spent a semester on a farm. I wanted to keep humans

from changing and destroying the planet. But geology complicated my

understanding of this desire. The planet has been changing for millennia.

It’s been destroyed and remade again and again. The temperature used to be

different. The continents were in different places. Different creatures

roamed the land. The environmentalist instinct to preserve the planet

exactly as it is began to seem not altruistic, but selfish. The planet is a

tough cookie. This pile of rocks doesn’t need saving. What we were trying to

save, it seemed, was the version of the planet that works best for

ourselves. And, sure, future generations and all the other species that

currently live here. Still a worthy goal, of course. Perhaps an even

worthier one, when you consider how unusual and unlikely Earth’s menagerie

is. But geology made me think about it in a new way.College students often enter university with an outsized view of their own

significance. It’s good to study things that make you realize how

unimportant you are. As a history major, I took a lot of classes that helped

me understand how small my life is in the span of human existence. But there

are a few courses—geology, astronomy, perhaps particle physics—that force

students to confront true vastness, that make you consider the

insignificance not just of your life, but of your entire species. Geology is

a gorgeous way to contemplate the abyss.This is valuable, in the end, because it both helps you care less and makes

you care more. What’s a bad day in the scheme of things? But then again, why

not make each one count? Something to consider, next time you contemplate

the contours of the land.

Indeed.

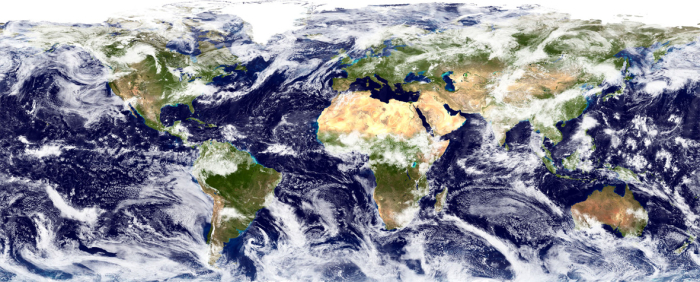

re the stunning image at the head of this post:

Credit: NASA Goddard Space Flight Center Image by Reto Stöckli (land surface,

shallow water, clouds). Enhancements by Robert Simmon (ocean color,

compositing, 3D globes, animation). Data and technical support: MODIS Land

Group; MODIS Science Data Support Team; MODIS Atmosphere Group; MODIS Ocean

Group Additional data: USGS EROS Data Center (topography); USGS Terrestrial

Remote Sensing Flagstaff Field Center (Antarctica); Defense Meteorological

Satellite Program (city lights)

This spectacular “blue marble” image is the most detailed true-color image of

the entire Earth to date. Using a collection of satellite-based observations,

scientists and visualizers stitched together months of observations of the

land surface, oceans, sea ice, and clouds into a seamless, true-color mosaic

of every square kilometer (.386 square mile) of our planet. These images are

freely available to educators, scientists, museums, and the public.

Much of the information contained in this image came from a single remote-

sensing device-NASA’sModerate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer,

or MODIS. Flying over 700 km above the Earth onboard the

Terra

satellite, MODIS provides an integrated tool for observing a variety of

terrestrial, oceanic, and atmospheric features of the Earth. The land and

coastal ocean portions of these images are based on surface observations

collected from June through September 2001 and combined, or composited, every

eight days to compensate for clouds that might block the sensor’s view of the

surface on any single day. Two different types of ocean data were used in

these images: shallow water true color data, and global ocean color (or

chlorophyll) data. Topographic shading is based on the GTOPO 30 elevation

dataset compiled by the U.S. Geological Survey’s EROS Data Center. MODIS

observations of polar sea ice were combined with observations of Antarctica

made by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s AVHRR sensor—the

Advanced Very High Resolution Radiometer. The cloud image is a composite of

two days of imagery collected in visible light wavelengths and a third day of

thermal infra-red imagery over the poles.

Originally published at: https://throughthesandglass.typepad.com/through_the_sandglass/science/