Sand and us

In the lively discussion period following the US premier screening of Sand

Wars in Washington DC a couple of weeks ago, and following the showing at the

Zurich environmental film festival, there was one outstanding theme –

surprise. Which is exactly what I had always hoped for with the book and then

with Denis Delestrac’s documentary. The fact that sand plays a heroic role in

our daily lives and the workings of our planet sets the scene for the – often

surprising – fact that sand is not just sand. Anyone who has occasionally

looked at this blog and, in particular, the displays of arenaceous diversity

in the Sunday Sand posts will appreciate that the stuff comes in a dazzling

variety of shapes, sizes and compositions – no two sands are the same. And

this means that if you want to make something with sand, whether it’s glass,

filters, concrete, golf course bunkers, foundry castings, silicon electronic

components, or a host of other things, any old sand just will not do: it has

to be the right kind of sand. Concrete, of course, is the most obvious

example, given how much of the stuff each of us uses (or has used on our

behalf). The fact that the rapid development of Dubai has only been possible

through sand imports when the desert dunes are right there, is a surprise. But

the fact is that desert sand just will not do for making good concrete.

The range of needs for special sands presents two challenges: how to get the

right kind of sand from the place where it naturally occurs to where it is

needed and how to ensure that the resources of that right kind of sand are not

only sustainable but exploitable without destroying the environment,

ecosystems and livelihoods. Meeting these challenges is manifestly failing in

many parts of the world, as the documentary describes, and, while it’s easy to

see this as a problem of the so-called developing world and that we in the

west are far too thoughtful in our approach to environmental and resource

management for such issues to arise at home, this is, sadly, not always the

case. A notable example is the supply of the specialty sand required – in vast

quantities – for the fracking (or fraccing) of oil and gas wells. This is an

emotional topic on both sides of the Atlantic and the subject of heated media

and social ‘debate’. This is not what my primary focus here is, but I should

probably declare my general position: fracking is proven and reliable

technology that presents problems only when regulations are loose, regulatory

enforcement is deficient, and ‘cowboy’ operators are allowed to flagrantly

disregard good engineering practice. The fact that these issues can be,

unfortunately, quite often the reality is a justifiable cause for concern –

it’s not rocket science to fix but the media frenzy is arguably misdirected.

Anyone who would like to discuss this further is more than welcome and I would

recommend having a look at the objective [report put out last year](http://royalsociety.org/uploadedFiles/Royal_Society_Content/policy/projects/shale-

gas/2012-06-28-Shale-gas.pdf) by The Royal Society and The Royal Academy of

Engineering. My point here, however, is specifically about sand.

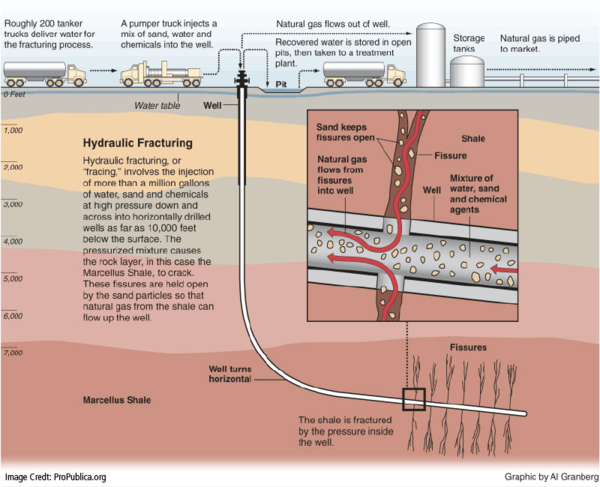

The technology of hydraulic fracturing involves accessing the oil or gas

trapped in essentially impermeable rocks from which they cannot naturally

escape. Permeability is induced artificially by water (and yes, also often

unknown chemical additives) under extremely high pressures, creating a network

of cracks, fractures, through which the hydrocarbons can be persuaded to

flow. But creating those fractures is only the start: natural underground

pressure would rapidly close them up again – something has to be put into them

that keeps them open, and that something is sand. But not just any old sand.

It has to be tough and uncrushable pure quartz sand, the grains have to be all

of the right size and they have to be smooth and rounded so that they don’t

clog up up the fluids or the fractures as they are forced into them. Here is a

view of a typical construction sand on the left next to a good frac sand:

The challenge lies in the fact that huge quantities of sand are required for

every fracturing operation – often thousands of tons per well. The whole

process is shown clearly in this graphic from the [Wisconsin Academy](https://www.wisconsinacademy.org/magazine/sand-

your-sand-sand-my-sand-0):

This demand, along with the enormous volume of water required, not does not

frequently feature as an issue in the ‘debate’. With the boom in fracking in

the US, demand for the right kind of sand has more than trebled in the last

four years – the US Geological Survey estimates that 30 million tons of frac

sand was produced in the US in 2013. Where from? Mostly Wisconsin and

neighbouring Midwestern states. The seas that covered much of the US more than

450 million years ago deposited, and time and chemistry purified, sands ideal

for hydraulic fracturing purposes. Although today these are sand stones, the

cement holding the grains together is weak and they can be easily mined and

disintegrated back into sand. The scale of the sand-mining industry in

Wisconsin and neighbouring parts of Minnesota has escalated dramatically in

the last few years to the point where it has clearly become an environmental,

social and health issue (the last particularly as a result of the generation

of silica dust). At the same time, the industry is a welcome source of

employment and state income, but fluctuations in the level of industry

fracking activity hardly make for a stable economic benefit. The image at the

head of this post is from a recent article by [Minnesota Public Radio](http://www.mprnews.org/story/2013/04/09/regional/frac-

sand-mining-slowdown) and shows two views of downtown Winona today and a year

ago when the stockpile of sand that became known as ‘Mt. Frac’ filled a vacant

lot. It has disappeared not because of the concerns rightly expressed by the

local citizens but because of the fall in demand.

As usual, these are issues that are not clearly one that is black-and-white,

but they could benefit from a little more awareness and careful discussion –

and not only in Wisconsin and Minnesota.

[For further reading, see this [Geology.com piece](http://geology.com/articles/frac-

sand/), a recent [article in Forbes](http://www.forbes.com/sites/christopherhelman/2013/08/22/a-new-

target-for-fracking-opponents-sand-mines/) , and this excellent [discussion from the Wisconsin

Academy](https://www.wisconsinacademy.org/magazine/sand-

your-sand-sand-my-sand-0) from which includes the two images within the post.]

Originally published at: https://throughthesandglass.typepad.com/through_the_sandglass/sand_and_us/page/2/