history

Tectonic turmoil has been a long-running production in Indonesia, even by

geological measures. Thirteen million years ago, peaceful seas covered what is

today eastern Java, but blundering plates soon put an end to the tranquillity.

The entire island of Borneo was rotating counter-clockwise, at the same time

suffering upheaval to the point where erosion became rapid and relentless.

Huge volumes of quartz-rich sands cascaded southwards into the seas of East

Java, burying the old, calm, seafloor in a thick blanket of shallow marine and

deepwater sands and mud. Eventually, the seas were entirely filled with these

sediments and rivers and deltas dominated what had been a marine environment.

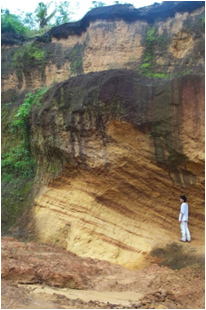

Continuing upheaval would eventually raise these sediments back above sea

level and expose them as sandstones in the river banks of eastern Java. They

are on particularly fine display not far from the village of Ngrayong which

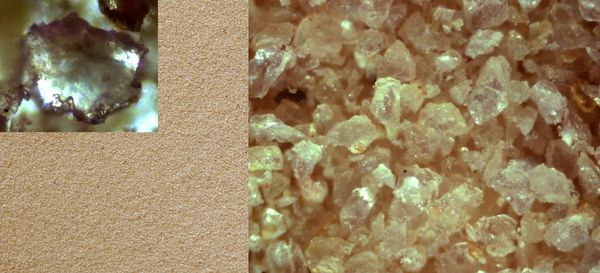

gave its name to this particular pile of sedimentary archives. The grains of

the Ngrayong sandstones are remarkably immature – they are sharp-edged and

angular, their journey having been too short for any effective abrasion and

rounding of those rough edges.

All of the grains in the images above are less than a fifth of a millimetre

across, very fine-grained components that have been separated from their

coarser companions by sieving. Why separate out these grains? Well, I came to

have a bag of this Ngrayong sand not because I have visited the location, but

because I was visiting the siever, so to speak; it turns out that these grains

perform particularly well in a rather intriguing experimental application –

but more of that for another post.

Where still buried underground, the Ngrayong sandstones themselves have also

performed rather well for more than a century as a reservoir for oil and gas.

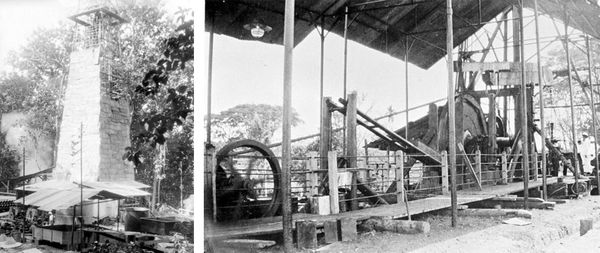

The original discoveries were made by the Dutch in the days of colonisation; I

did visit these old fields many years ago when I was in Indonesia before, for

they are still producing and more discoveries, some of them very large, are

still being made. But the real fascination was the in situ museum of

industry history that the area represented – pieces of old equipment,

venerable wheezing pumps and groaning fly-wheels still sedately in action.

Unfortunately, all those photographs are in my archives back in London, but

here are a couple of images from the 1920s, courtesy of the Tropenmuseum in

the Netherlands.

Originally published at: https://throughthesandglass.typepad.com/through_the_sandglass/history/page/2/