Extraterrestrial

The last [Sunday Sand post](https://throughthesandglass.typepad.com/through_the_sandglass/2011/02/sunday-

sand-bagnolds-grains.html) returned to the ever-fascinating work and exploits

of Ralph Bagnold; after writing it, I was catching up on arenaceous research

news and there he was again – on Mars, so to speak. A recent [press release](http://www.psi.edu/news/press-

releases/hansen.html) from the Planetary Science Institute and the Mars HiRise

imaging team announces “to their surprise” that seasonally repeated imagery

reveals that the polar dunes of the planet are constantly changing. Why should

this be a surprise? After all, dune systems on Earth are among the most

dynamic landscapes on the planet – why should Mars be any different? Well,

there are important differences, as we shall see, but that Martian dunes have

been “long thought to be frozen in time” is the real surprise – and is shown

to be unfounded. Yes, seasonal icing stabilises the dunes, but melting and

degassing causes instability – and the wind re-sculpts the surface.

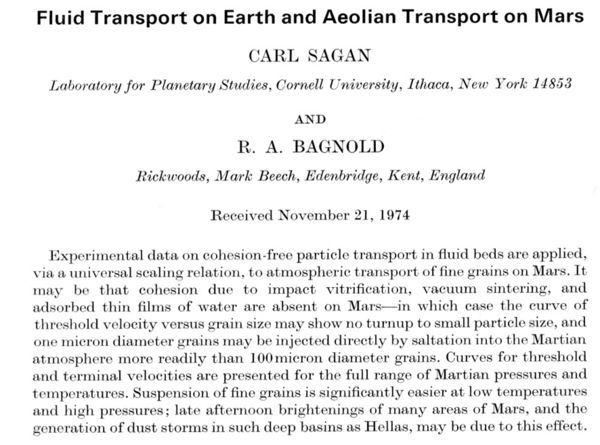

Nor should we be surprised that Bagnold enters the arena of this debate for,

while his seminal work on the physics of windblown sand was first published

seventy years ago, it remains the foundation of aeolian research today, his

basic equations and analysis of processes refined but essentially unchanged.

And we should also not be surprised that his work applies as well to Mars as

it does to Earth – after all, he was called in as an advisor to NASA during

the planning of the early Mars missions and, in 1974, he published a paper

with Carl Sagan comparing transport on the two planets:

In this paper, as apparent in the abstract, the interest is in threshold

velocities of the wind – how strong a wind is necessary to move sand? This is

a complex topic, but Bagnold’s work on Earth reveals the keys to understanding

sand dynamics on Mars, as revealed by this recent press release – particularly

when combined with research results published last year.

But first, back to Bagnold basics. During his extraordinary expeditions, he

closely observed the characteristics of dune architecture and movement, and

came to appreciate that there were a number of fundamental questions that, at

that point, had not been answered. One of the most basic of these questions

was why do dunes form at all? Why is the sand not spread evenly over the

desert floor? Whether on Earth or Mars (or, indeed, Venus or Titan), dunes

appear to be self-accumulating , seeming to vacuum up sand from the bare

stony areas between them – they grow by attracting more sand. “Why did they

absorb nourishment and continue to grow instead of allowing the sand to spread

out evenly over the desert as finer dust grains do?” was one of Bagnold’s

questions. This was, he thought, something that “could be explored at home in

England under laboratory-controlled conditions” - and so began his rigorous

science. Two of the most important revelations of Bagnold’s work are the

process of saltation and the role of two different threshold velocities for

the wind.

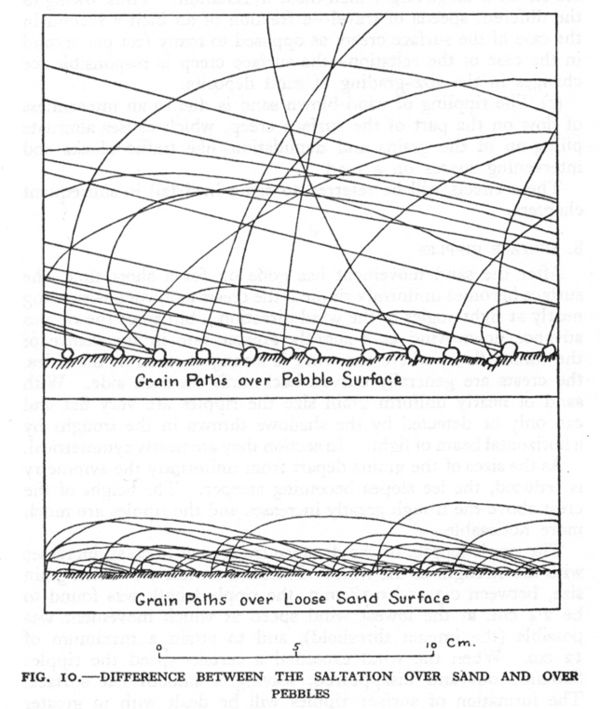

First, saltation. From the Latin verb “to jump,” this is the process whereby

sand grains move in the wind by individual leaps, and, landing on a hard

surface, bounce off again; if a grain lands amongst other grains on the

surface of a dune, the impact kicks some of them up into the wind and the

crowd of flying grains grows. It is these two contrasting behaviours –

bouncing versus splashing – that explain the self-accumulating nature of

dunes. Over a hard surface of rocks and pebbles, the trajectories of

individual grains are high into the air, and they keep on bouncing. As soon as

they hit a soft surface of a dune, they kick off more grains, but the

trajectories are lower and shorter – the dune grows. Here’s Bagnold’s original

illustration of this:

So, saltation is the key activity of windblown sand. But how does it start?

Clearly, if the wind blowing over a surface of sand is strong enough, it will

nudge, roll, and pick up grains until the self-sustaining process of saltation

begins. The wind speed at which this starts Bagnold referred to as the “fluid

threshold” – and it represents a pretty strong wind. But , once grains are

saltating and being kicked up into the wind, it only needs a slower velocity

to keep the process going – lower the wind speed to the point where all grain

motion stops, and that is the “impact threshold,” the minimum velocity to keep

sand in motion – and it’s much lower than the fluid threshold.

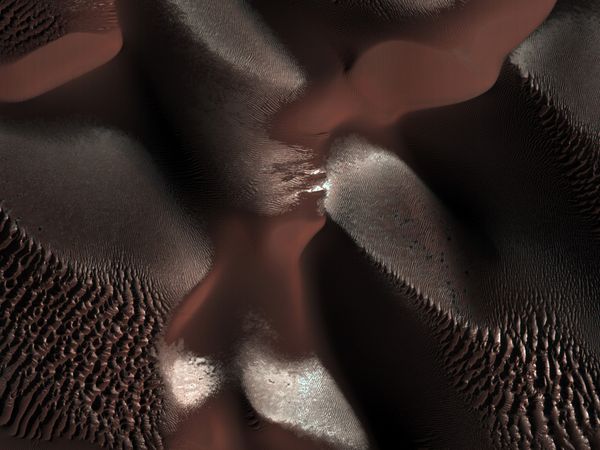

So, back to Mars. The three sequential images at the head of this post show

clear changes in the dune as the thawing of winter carbon dioxide ice

destabilises the structure. The caption is as follows:

Three images of the same location taken at different times on Mars show

seasonal activity causing sand avalanches and ripple changes on a Martian

dune. The High Resolution Imaging Science Experiment (HiRISE) camera on

NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter took these images, centered at 84 degrees

north latitude and 233.2 degrees east longitude. Dune fields at high

latitudes are covered every year by a seasonal polar cap of condensed CO2

(dry ice).The sequential images, which each show an area 285 meters by 140 meters,

depict the before and after morphology of the dune in one Mars year, with

new alcoves and extension of the debris apron on the slipface, or steeply

sloping leeward surface, of the dune caused by the grainfall, and new wind

ripples on the debris apron.The top image was taken first, in the Martian summer when the dunes were

free of seasonal dry ice. The middle image was acquired in the spring when

the region was covered by a layer of seasonal ice. Spring evaporation of the

seasonal layer of ice is manifested as dark streaks of fine particles

carried to the top of the ice layer by escaping gas. Gas flow under the ice

as the ice sublimates – changes from solid to gas – from the bottom

destabilizes the sand on the dune, and causes the sand to avalanche down the

dune slipface.The third image shows the resulting changes revealed the following summer

after the frozen layer of ice was gone. Comparison of the middle and lower

images shows the correlation of seasonal activity with locations of change

of dune morphology.

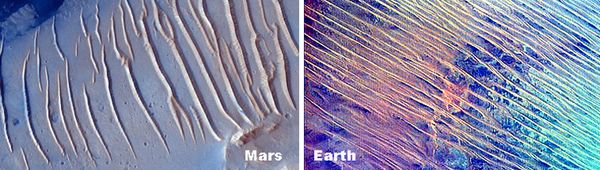

The emphasis here is on the avalanches down the side of the dune. But these

are – hardly surprising – gravitational effects, even under the relatively low

gravity of Mars; what is perhaps more surprising is the brief mention of “new

wind ripples on the debris apron.” Conventional wisdom and standard Martian

climate models had held that wind speeds on Mars were rarely adequate to cause

sand movement; measurements from landers confirmed relatively modest winds –

and yet sand grains have accumulated on the deck of Spirit , the [stuck rover](https://throughthesandglass.typepad.com/through_the_sandglass/2009/12/free-

spirit-update-things-are-looking-worse.html), and now we see dynamic ripples.

Enter, firmly in the footsteps of Ralph Bagnold, Jasper Kok,

an atmospheric physicist at the National Center for Atmospheric Research in

Boulder, Colorado (previously at the University of Michigan). Last year, he

published the results of his work on sand transport on Mars and the key roles

of different threshold velocities. He pointed out that the focus of Martian

modelling had been on the fluid threshold, the velocity required to start

saltation, but that little attention had been paid to the impact threshold,

above which any saltation already happening would be sustained. His work

demonstrated that ““While it is very difficult for the wind to lift sand

grains, once the wind does become strong enough to start blowing sand on Mars,

the sand will keep bouncing, even when the wind speed drops by up to a factor

of 10.” Because of the thin atmosphere (and coupled with the low gravity),

while Martian sand grains need hurricane-strength wind speeds of 150 km/h to

start moving, they will keep bouncing over the surface at wind speeds of just

15 km/hour. The conspiracy of the difference in parameters between Earth and

Mars means that the fluid thresholds are little different – but the impact

threshold is far lower of the red planet: windblown sand processes are alive

and well – and, now, observable. Take into account different grain sizes and

differing saltation trajectories, and Kok’s work (see references at the end of

this post) also begins to explain the smaller dunes apparently typical of

Mars, and the complex relationships between sand and dust movement, not to

mention [dust devils](https://throughthesandglass.typepad.com/through_the_sandglass/2010/09/its-

all-about-size-martian-dust-devils.html).

So, once again, conventional wisdom is out the window, but the wisdom of Ralph

Bagnold endures; in Kok’s papers, the bibliography includes citations of

Bagnold’s work from seventy years ago – how often do you see that?

[Read Jasper Kok’s papers here

and

here,

and reports of his work at Physics World

and [Wired Science](https://www.wired.com/wiredscience/2010/02/martian-

dune-mystery-solved-by-bouncing-sand-grains/); for summaries of the recent

HiRise sequential imaging, see, for example, Mars Daily

and

[Wired](https://www.wired.com/wiredscience/2011/02/mars-

shifty-sand-dunes/). Images and more at http://hirise.lpl.arizona.edu/]

Originally published at: https://throughthesandglass.typepad.com/through_the_sandglass/extraterrestrial/page/2/