Sunday sands

There’s only one major sand dune field on the Colorado Plateau, and that can

be found at the Coral Pink Sand Dunes State Park, way down in the southwest

corner of Utah, not far from Zion National Park. And are these dunes really

coral pink? Or reddish orange? Or orangey pink? Opinions vary – as do the

colours of the sand depending on the light and the time of day. But their true

colour hardly matters – they are impressive dunes.

Formed

Formed

perhaps 10,000 years ago, as the northern ice was beginning to recede, their

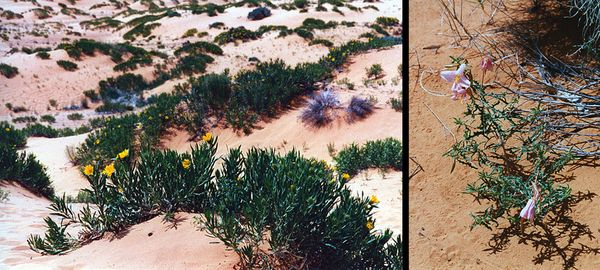

sands are home to a diversity of plants and animals, including the charming –

but severely threatened – Coral Pink Sand Dunes tiger beetle, Cicindela

albissima, only recently promoted to a species in its own right, and which is

only found in these dunes.

The sand grains are typical of a windblown heritage, smoothed, frosted, and

rounded by the endless mutual abrasion as they are buffeted by the wind. And

they are all more or less of the same size – the finer grains are blown

onwards, the coarser ones left behind; and they are essentially all quartz.

It’s the local winds that explain why these dunes are where they are. Just to

the north-east of the dunes is a significant “notch” in the ranges of the

plateau. The prevailing winds blast sand south-westwards, are funnelled

through the notch, and, as they emerge and diminish, can no longer carry the

sand, dropping it to feed the dunes. If you look at this on Google Earth, you

can almost feel the sands streaming through the gap in the hills:

And why is that gap there? Well, because one of the great geo-architectural

features of the Colorado Plateau, the Sevier Fault, cuts through it. The fault

is a huge fracture in the earth’s crust, over a hundred kilometres long, and

almost vertical; everything to the west of the fault has dropped down 700

meters (2300 feet) relative to the rocks on the east. The fault is clearly

visible on the satellite image below, right, as a scar slicing across the

landscape:

On the left is exactly the same area but shown as a geological map, the rocks

of different ages appearing in different colours, the faults as black lines.

To the east of the Sevier fault, the landscape is dominated by the light blue

rocks of the Navajo Sandstone, to the west, the green of the Carmel Formation,

mostly made up of limestones. The Navajo was deposited during the Lower

Jurassic, around 185 million years ago, the Carmel later, on top of it, around

165 million years ago. So the map shows clearly that the movement on the

Sevier fault is down to the west – the rocks of the Carmel are younger than

the Navajo in the hills to the east, and have been completely removed by

erosion on the uplifted side of the fault.

It’s a big and complex fault system, and the grinding of fault movement would

have pulverised the rock along the fault zone, leaving it weaker and exposed

to erosion – hence the gap through which the sands blow. And the Sevier fault

is still on the move – it has been seismically active for a long time, part of

the so-called intermontane seismic belt.

So, we have figured out why all those sand grains are piled up where they are,

but what’s their story? The photo below shows the dunes in the foreground and,

in background, the pink sandstones of the Navajo Sandstone on the east side of

the fault. Look carefully and you will recognise dunes ancient and modern.

The Navajo is an iconic formation, the star of the landscapes of many of

Utah’s national and state parks. It represents an enormous erg, a large sand

sea that extended over most of Utah as well as parts of New Mexico, Arizona,

Colorado and Wyoming. Look carefully at the bluffs in the photo, and you can

see gigantic scale cross-bedding, signalling wind-blown sand, dunes. Excavate

the dunes of the Coral Pink Sand Dunes (in your imagination), and exactly the

same structures will be revealed – the vital principle of uniformitarianism at

work. That principle derives from the observations of James Hutton in the late

18th century, that the processes we see today sculpting the surface of our

planet have always operated, and always will. Commonly summarised as “the

present is the key to the past,” it has been debated and refined ever since –

for example, the rates at which a process, e.g., global volcanism, operated

have varied over time – but the principle is, indeed, the key to our being

able to read the ledgers of earth’s history. Winds have always blown, sand has

always been on the move, dunes have always been built in the same way.

The bluffs of ancient Navajo dunes in south-western Utah have been exposed to

the attack of weathering and erosion for a long time, disintegrating and

liberating the tough little sand grains. Those grains have been swept along by

rivers, left in sand banks, dried out, and picked up by the wind for the next

stage of their travels – to the Coral Pink Sand Dunes State Park. There they

rest, for a while, on their never-ending journey, and what you see in those

dunes today are re-cycled grains from a desert nearly two hundred million

years ago.

[Heartfelt thanks to Myrna and Charles Gifford for collecting and sending the sand, and for the photographs.

Beetle image from the [US Fish and

Wildlife](https://www.fws.gov/mountain-

prairie/species/invertebrates/CoralPinkSandDunesTigerBeetle/index.html)

Service; geological map from the superb Utah Geological Survey interactive map

site;

for resources on the Coral Pink Sand Dunes State Park, see

[here](http://www.stateparks.utah.gov/parks/coral-

pink),

here,

and

here.]

Originally published at: https://throughthesandglass.typepad.com/through_the_sandglass/sunday-sands/